Unveiling the Enigmatic History of Odisha: A Fascinating Journey Through Time

The history of Odisha, also known as Orissa, can be traced back to ancient times. The region has a rich and diverse history spanning several centuries. Odisha, located on the eastern coast of India, is a land of enchanting beauty and historical significance. Its history is a tapestry woven with threads of art, culture, religion, and resilience. In this article, we embark on a journey through time, exploring the fascinating chapters that have shaped the identity of Odisha. Here is a brief overview of the history of Odisha:

Uncovering the Enigmatic Past of Odisha: A Journey Through Time

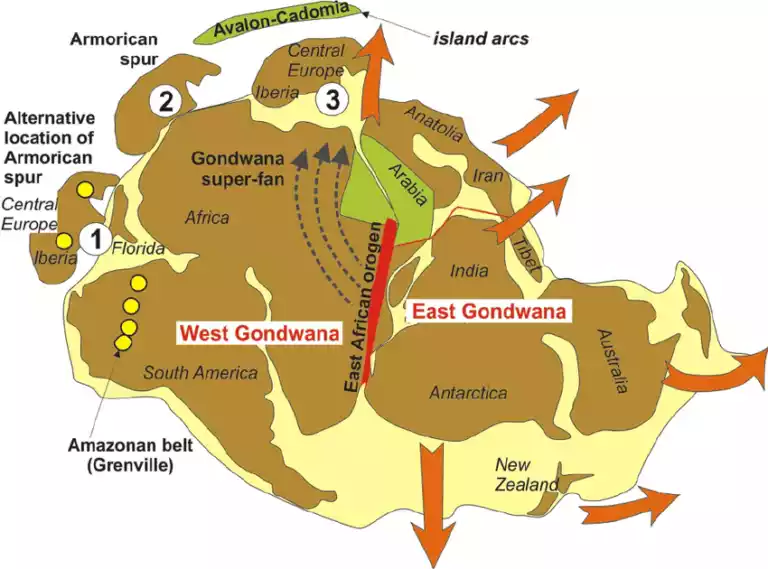

Nestled within the heart of India, the modern-day state of Odisha holds a secret that traces back a staggering 140 million years. This story begins in a world where Odisha was not a distinct entity but an integral part of a colossal supercontinent known as Gondwanaland. The very name “Gondwanaland” finds its roots in the region we now refer to as Gondwana, a term derived from the indigenous Gondi people, who continue to inhabit not only Odisha but various other regions across India.

The ancient tale of Gondwanaland unravels through the rocks, some of which have endured the test of time for an astonishing 3.09 billion years. These ancient formations, such as the Mayurbhanj granite pluton, serve as relics from a distant past, offering a window into the Earth’s primordial history.

Within the Mahanadi and Ib River basins, Odisha boasts vast coal-rich landscapes, which have gained fame for preserving a treasure trove of ancient fossils. Imprints of prehistoric civilizations surface in the form of Acheulian tools, unearthed in places like Mayurbhanj, Keonjhar, Sundergarh, and Sambalpur, dating back to the Lower Paleolithic period.

Venture into the Gudahandi hills of Kalahandi district, and you’ll encounter rocks adorned with intricate carvings and paintings, relics from the Upper Paleolithic era, bearing testament to the artistic expression of ancient inhabitants.

In the vicinity of Baripada, specifically in Kuchai, a diverse array of ancient tools like hoes, chisels, pounders, mace heads, grinding stones, and pottery fragments harken back to the Neolithic period, shedding light on the skills and craftsmanship of early societies.

In select districts like Sundergarh, Sambalpur, and Jharsuguda, rocks harbor ancient paintings and enigmatic inscriptions, with speculations swirling around whether the writings at Ushakothi and Vimkramkhol belong to a script known as proto-Brahmi.

Finally, journey near Khariar, where the walls of Yogimath cave bear witness to Neolithic-period cave paintings. These murals provide a captivating glimpse into the vibrant cultures and artistic expressions that once flourished in this region.

In summary, Odisha’s history is a tapestry woven with threads from ancient epochs, a rich and diverse heritage that spans millennia, offering a captivating narrative of human civilization and evolution.

The Epic Tale of King Bali and the Kingdoms of Mahabharata

In ancient legends such as the Mahabharata, there existed a king named Bali, who faced a unique predicament – he had no male heirs to carry on his legacy. In his quest to secure his lineage, he sought the wisdom of a venerable sage known as Dirghatamas. The sage, along with his wife Queen Sudesna, was blessed with five sons, namely Anga, Vanga, Kalinga, Sumha, and Pundra.

As time unfolded, these five sons embarked on their own remarkable journeys, establishing kingdoms named after themselves. Notably, Prince Vanga founded the illustrious Vanga kingdom, encompassing what is now modern-day Bangladesh and parts of West Bengal. Meanwhile, Prince Kalinga’s endeavors led to the establishment of the Kalinga kingdom, situated along the coastal regions of Odisha, including the North Sircars.

Within the Mahabharata, Kalinga makes recurring appearances, shedding light on its significance in the epic narrative. Among its notable figures was King Srutayudha, the offspring of Varuna and the river Parnasa. During the momentous Kurukshetra War, Srutayudha allied himself with the Kauravas and wielded a formidable weapon – a mace gifted to him by his father. This mace possessed the power to protect its wielder but came with a crucial stipulation – it could only be used against combatants.

In the midst of the fierce battle, driven by the onslaught of Arjuna’s arrows, Srutayudha inadvertently erred, deploying his mace against Krishna, who stood unarmed, steering Arjuna’s chariot. Astonishingly, the mace recoiled from Krishna, ultimately leading to Srutayudha’s demise. This tragic event set in motion a chain of events that would culminate in Krishna’s eventual demise, orchestrated by a man named Jara Savara and another figure known as Ekalavya. It is worth noting that both Jara Savara and Ekalavya are believed to have hailed from the Sabar people of Odisha.

The Ancient Rule of Mahapadma Nanda

In a bygone era, a man named Mahapadma Nanda held sway over the land of Magadha. Historical records indicate that around 350 BCE, he extended his dominion to encompass the region of Kalinga. Remarkably, the Hathigumpha inscriptions, etched into a cave wall, offer valuable insights into the Nanda rulers’ administration of Kalinga. These inscriptions not only shed light on their governance but also reveal their ambitious agricultural initiatives, aimed at harnessing the power of water for the benefit of the land during their reign.

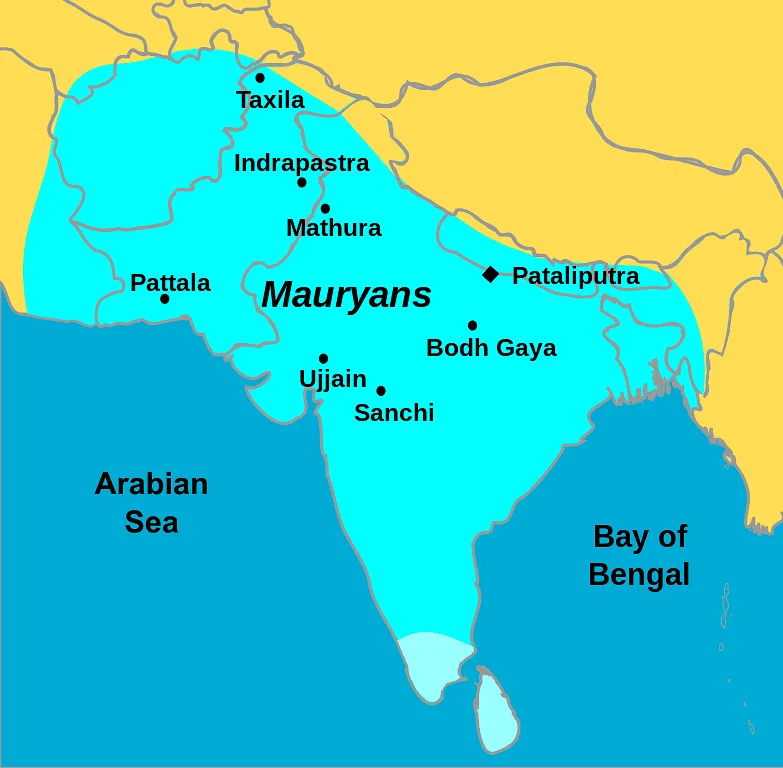

Mauryan (350 BCE)

Ashoka was a powerful king from a long time ago. He fought a really big and brutal war in a place called Kalinga in 261 BCE. Lots of people died, got captured, and suffered during this war. It made Ashoka feel really bad.

Because of this war, Ashoka decided to change. He stopped being a warrior and became a peaceful person. He also started following Buddhism, a peaceful religion. But some people think he was already interested in Buddhism before the war. It seems like he became a Buddhist because he wanted to become king and not because he felt sorry for the war’s suffering.

During the war, some people from a place called Atavika helped the Kalingans. After the war, Ashoka took control of the coastal part of Kalinga but didn’t try to take over the Atavika region. He ruled Kalinga like a province, with Tosali as the main city where they made important decisions. A leader called a ‘kumara’ ruled from Tosali, which is like a governor. There were also other important places like Samapa.

Ashoka put up two special messages in this area, one at Jaugada and one at Dhauli.”

So, in simple terms, it’s about Ashoka, a king who had a big war, felt bad about it, and changed his ways. He might have converted to Buddhism for political reasons, and he ruled a place called Kalinga.

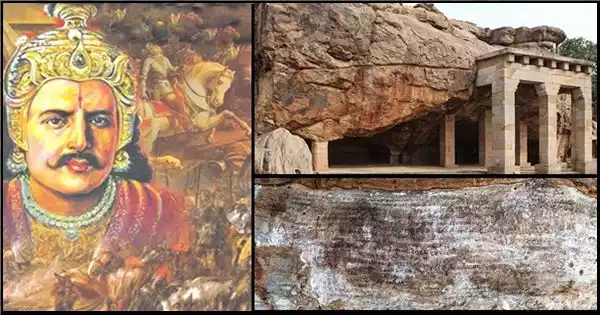

Kharavela(1st century BCE)

In ancient times, around 170 BCE, there was a king named Kharavela who ruled a place called Kalinganagari. He became king when he was 24 years old. During his rule, he did many important things.

In the first year of being king, he fixed the walls and gates of his capital city, which were damaged in a storm. In the second year, he attacked a city called Musikas that belonged to another king named Satakarni I. He also marched near a river called Kanha-bemna.

In the third year, he organized music and dance performances to make his people happy. In the fourth year, he attacked Satakarni I again and became more powerful in that region. In the fifth year, he fixed an old water system that was built 300 years ago.

In the sixth year, he reduced taxes and helped people in cities and villages. In the seventh year, something important happened – his main queen had a baby. In the eighth year, he went to fight a king named Rajagaha. At that time, another group called the Yavana (Indo-Greeks) were coming towards Pataliputra. But when they heard that Kharavela had won, they ran away.

Kharavela chased them and took back a place called Mathura, which was important for Jain religion and culture. To remember this, he built a special palace in Kalinga.

In the eleventh year, he defeated a place called Dramira, which had been around for 113 years before his time. In the twelfth year, he went to northern India again and even went up to Uttarapatha. On his way back, he scared the people of Magadha, and their king surrendered. Kharavela brought back a special statue called Kalinga Jina, which was taken away from Kalinga a long time ago.

In his thirteenth year as king, Kharavela made homes in caves for Jain monks and gave them money. Jainism became very strong in Kalinga because of Kharavela. He also helped people of other religions and repaired many temples. He built caves at Udayagiri and Khandagiri for Jain monks. Kharavela was known as a great king who respected all religions and took care of his people.

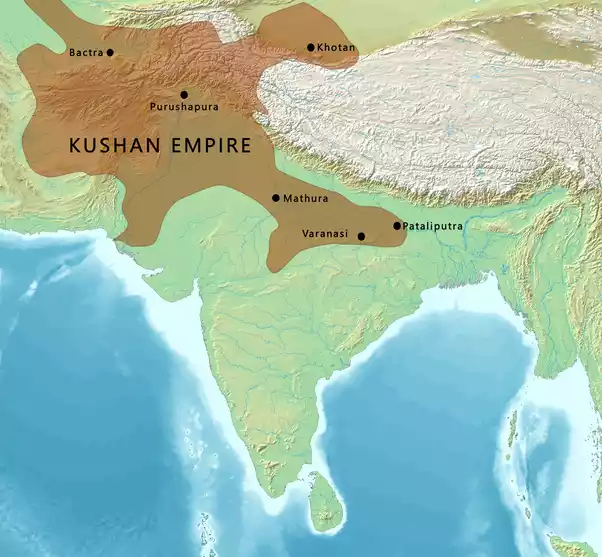

Kushan Empire’s Possible Influence on Kalinga

In ancient times, during the first few centuries AD, there are intriguing indications that the far-reaching Kushan Empire extended its influence to Kalinga, a region in India. The evidence for this fascinating historical connection lies in the discovery of coins resembling Kushan currency in various locations such as Jaugada, Sisupalgarh, and Gurubai in Manikapatana (Puri). However, what piques our curiosity is the prevalence of counterfeit coins outnumbering authentic ones. This leads us to speculate that local rulers might have continued to employ these imitation coins even after the decline of the Kushan Empire.

Among the remarkable findings, one coin stands out, bearing the name of Maharaja Rajadhiraja Dharmadamadhara. On one side of this coin, an intricately designed Kushana motif graces its surface, while the other side features the image of a human head.

Around the 3rd century, the reins of power shifted to a tribe known as the Murundas, who held sway over Pataliputra. Some scholars suggest that these enigmatic rulers may have hailed from Central Asia, further deepening the historical enigma. Intriguingly, they minted coins strikingly similar to those of the Kushan Empire. Yet, despite these tantalizing coin discoveries, this era remains shrouded in historical obscurity.

In simplified terms, the unearthing of these coins hints at the possibility of the Kushan Empire’s far-reaching influence in Kalinga’s ancient past. The enduring usage of these coins by local leaders even after the empire’s decline adds an intriguing layer to this historical puzzle. Additionally, the Murundas, with their uncanny coin resemblance, add yet another layer of mystery to this enigmatic chapter in history. Overall, this period remains a captivating and unresolved historical riddle.

Guptas, Matharas, and Sharabhapuriyas

In around 313 BCE, there was a princess named Hemamala from a place called Kalinga. She did something remarkable. She secretly took one of Buddha’s teeth, which was a very sacred thing, and hid it in her hair. Later, she gave this tooth to a king named Brahmadutta. This king built a temple for it in a city called Dantapura. Many years passed, and during the time of a prince named Guhasiva, a prince from Ujjain came to Dantapura to worship this sacred tooth. He fell in love with Guhasiva’s daughter, Hemamala, and they got married. He became known as Dantakumara, which means “Prince Tooth.”

When another king tried to attack Kalinga, Dantakumara and Hemamala had to flee with the sacred tooth to protect it.

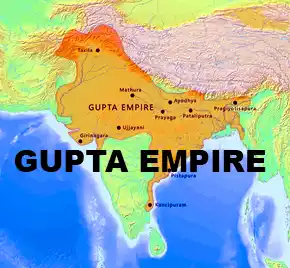

A long time later, around 335 to 375 CE, a king named Samudragupta is thought to have conquered the region. He mentioned in his writings that he had conquered various places, including what is believed to be the capital of Kalinga, Pishtapura. Other areas like Mahakantara and Kottura were also part of this region.

After Samudragupta’s time, a new dynasty called the Matharas ruled in south Kalinga. They controlled the area from Mahanadi to Godavari.

In western Odisha, another dynasty called the Sharabhapuriya dynasty emerged during the post-Gupta period. Not much is known about them except for what’s written on copper plates and coins. They might have also been known as the Amararyakula dynasty. They ruled over areas like Raipur, Bilaspur, and Kalahandi from around 499 to about 700 CE.

Shailodbhava dynasty

The Shailodbhava dynasty was in charge of a place called Kongoda-mandala in what is now Odisha from the 6th to the 8th centuries. Their main area included parts of Ganjam, Khordha, and Puri districts. They ruled from Kongoda, which is now known as Banapur. At first, this region was made a province by the Gauda king Shashanka after he conquered Odisha. He made Madhavaraja II the ruler of this area.

Madhavaraja II later became independent, even though it’s not entirely clear if he took control of the entire Kalinga region, as another king named Indravarman also claimed to have done so during the same time. Madhavaraja II left inscriptions suggesting he performed certain rituals to show his independence. His son, Dharmaraja, followed him and ruled for at least 30 years, taking on impressive royal titles.

As time went on, the Shailodbhava dynasty became less well-known, and their land seemed to become part of another kingdom called the Shvetaka Gangas. These new rulers were under the Bhauma-Kara kingdom by the 8th century.

In simple terms, the Shailodbhava dynasty ruled a part of Odisha long ago, and they started as subordinates but later became independent. Eventually, their power faded, and another kingdom took over the area.

Bhauma-Kara dynasty

The Bhauma-Kara dynasty ruled in parts of Odisha, India, from the 8th to the 10th centuries. Their kingdom was called Toshala. At first, they followed Buddhism, but later they embraced Shaivism and Vaishnavism.

In the 8th century, they took control of the Shailodbhava territory. The early Bhauma-Kara kings ruled the northern Toshali area, while the Shailodbhavas ruled the southern Kongoda region. By the time of King Shivakara I, around 756/786, they ruled most of coastal Odisha and even conquered Kongoda and northern Kalinga.

Shantikara I, the son of Shubhakara I, married Tribhuvana Mahadevi I, who was the daughter of the Western Ganga king Rajamalla. The Dhenkanal inscription of Tribhuvana-Mahadevi I in 846 talks about the troubled times in the Bhauma-Kara kingdom before her father Rajmalla helped end the Rashtrakuta-Pala rule. She united the kingdom, and her successors started bringing together historically separate regions like Odra, Toshala, Kongoda, and Utkala during the Bhauma-Kara period.

The Somavamshi Dynasty: Rulers of Ancient Odisha

The Somavamshi dynasty, also known as the Keshari dynasty, held sway over significant parts of present-day Odisha in eastern India from the 9th to the 12th centuries. Their dominion encompassed regions such as Yayatinagara (now modern Binika) and Abhinava-Yayatinagara (now modern Jajpur). The early Somavamshi monarchs governed the eastern part of Dakshina Kosala, which today comprises a substantial portion of western Odisha.

Janamejaya, the earliest known Somavamshi king, is described in the Chaudwar inscription as ‘Kosalendra,’ signifying his status as the lord of Kosala. During his extensive 34-year reign, Janmejaya issued numerous copper-plate grants across western and coastal Odisha. This suggests that Janmejaya successfully consolidated Somavamshi rule in western Odisha. By his 31st year on the throne, he had issued three grants from Kataka, identified as Chaudwar near modern Cuttack, indicating his influence had expanded to eastern Odisha.

Yayati I, Janmejaya I’s son, reigned from approximately 922 to 955 and made substantial grants in Dakshina Kosala, documented in inscriptions from Yayatinagara. The capital later shifted to Guheshvarapataka (modern Jajpur) following the conquest of the Bhauma-Kara kingdom. In light of this triumph, the city was renamed Abhinava-Yayatinagara, signifying the new city of Yayati. Yayati I is credited with constructing a new temple in Puri and installing the image of Purushottama (Jagannatha) within it. His reign marked the inception of the Somavamshi style of temple architecture in Odisha, characterized by innovative ornamentation and iconography.

An epoch of significance during Yayati I’s reign was the commencement of the Utkaliya era, which appears to align with the rule of the legendary early Somavamshis (Kesaris), as indicated in the chronicle Madala Panji. This marks the initiation of the Odia calendar era.

Historical Significance of the Eastern Ganga Dynasty in Kalinga

The Jagannath temple, a renowned architectural marvel, stands as a testament to the rich history of the Eastern Ganga dynasty. This dynasty, with roots tracing back to ancient times, played a pivotal role in shaping the cultural and political landscape of Kalinga (present-day Odisha) and beyond.

Founding Figures Narasimhadeva I, a prominent ruler of this dynasty, is credited with the construction of the iconic Konark temple. However, the dynasty’s origins are rooted in the enigmatic figure, Indravarman I, assumed to be the earliest known king of the Eastern Ganga dynasty. His historical significance lies in his Jirjingi grant, which intriguingly mentions no predecessors. This grant, issued during his 39th regnal year around 537 CE, provides a glimpse into the dynasty’s early days. Notably, Indravarman I’s capital was located at Dantapura, marking the initial center of power.

Triumphant Legacy The Eastern Ganga dynasty saw many rulers adopting the title of “Trikalingadhipati,” signifying their authority over the three Kalingas. Over time, the dynasty’s capital shifted to Kalinganagara, notably during the reign of Devendravarman I, who ruled from c. 652 to 682 CE. This shift marked a significant chapter in the dynasty’s evolution.

A Glimpse Through Xuanzang’s Eyes Around 639 CE, the renowned Chinese Buddhist monk Xuanzang ventured into this region, leaving behind invaluable historical records. He noted that Buddhism thrived in this area, mentioning the existence of the Puphagiri monastery. These sites remained hidden until recent excavations unearthed numerous Buddhist monuments from this era.

Chola Conquest In the early 11th century, Rajendra Chola I, a formidable ruler from the Chola dynasty, conquered Odisha, ushering in a new era of influence and change.

Puri Jagannath Temple’s Genesis The capital shifted once more to Kataka (modern-day Cuttack) under the rule of Anantavarman Chodaganga in 1135. He initiated the construction of the iconic Puri Jagannath temple, a masterpiece of architecture and devotion. The temple’s completion was carried out by his successor, Anangabhima Deva III. Narasingha Deva I also made his mark by building the awe-inspiring Konark temple.

Kalinga’s Influence Beyond Borders In 1187, Nissanka Malla, who claimed descent from Kalinga, ascended to the throne in Sri Lanka, highlighting Kalinga’s influence beyond its geographical borders. His origins can be traced to the capital of Kalinga, Sinhapura (modern-day Srikakulam in Andhra Pradesh), where he might have been born in 1157.

Kalinga’s Impact on Sri Lanka In 1215, Kalinga Magha, an invader from Kalinga, established a reign of 21 years in Sri Lanka, leaving an indelible mark on its history.

Kalingathu Parani: Literary Tribute to Conquest During the early 12th century, Kalinga faced conquest by Kulothunga Chola I and his esteemed general, Karunakara Tondaiman. This historical episode is celebrated in the literary work called “Kalingathu Parani,” a tribute to the Chola invasion.

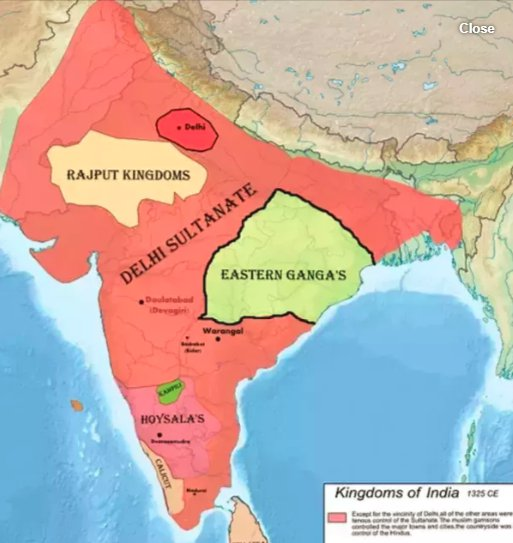

Turbulent Times The text “Tabaqat-i Nasiri” documents a turbulent period when the ruler of Jajnagar (Kalinga) clashed with the ruler of Lukhnauti (Bengal) in 1243. Tughral Tughan Khan, the governor of Bengal, led an expedition against Jajnagar in March 1244. After a month-long standoff at the frontier fort of Katashin, the Kalingan army eventually withdrew. However, a surprise attack by the Kalingan forces during Khan’s army’s lunch led to their defeat and retreat.

In summary, the Eastern Ganga dynasty’s historical significance transcends time, leaving behind a rich legacy of culture, conquests, and architectural wonders that continue to captivate modern-day enthusiasts and historians alike.

The Rise and Fall of the Gajapati Empire: A Historical Overview

The Gajapati Empire, established in 1435 by Kapilendra Deva, marked a significant chapter in Indian history. This dynasty, also known as the Suryavamsi dynasty, thrived in the wake of the Eastern Ganga kingdom’s decline. In this article, we will delve into the key events and rulers that shaped the Gajapati Empire’s trajectory.

- Kapilendra Deva’s Expansion (1435-1457): Kapilendra Deva, the founder of the Gajapati Empire, wasted no time in consolidating his power. Following the fall of the Eastern Ganga king, Bhanudeva IV, in 1435, he ascended to the throne. By 1457, Kapilendra Deva had expanded his realm significantly, stretching from the Ganga River in the north to Bidar in the south.

- Literary Flourishing under Kapilendra Deva: Kapilendra Deva’s reign was not just about territorial expansion; it also witnessed cultural blossoming. During this era, Sarala Das, an Odia poet, penned the Odia Mahabharata and other notable works, leaving a lasting literary legacy.

- Succession Struggles (1467-1484): Upon Kapilendra Deva’s demise in 1467, a fierce civil war ensued among his sons to claim the throne. Ultimately, Purushottama Deva emerged victorious in 1484 after defeating Hamvira.

- Challenges from the South (1484-1497): While Purushottama Deva secured the throne, the Gajapati Empire faced challenges from the south, particularly from Saluva Narasimha, the ruler of Vijayanagara. However, by the time of his death, Purushottama Deva had managed to reclaim most of these lost territories, successfully countering the Vijayanagara threat.

- Prataparudra Deva’s Reign (1497-1541): In 1497, Prataparudra Deva succeeded his father and had to immediately confront Alauddin Husain Shah of Bengal’s armies. Throughout his reign, Alauddin Husain Shah launched multiple attacks, with the Muslim army marching up to Puri in 1508.

- The Vijayanagara Incursion (1512): In 1512, Krishna Deva Raya of the Vijayanagara Empire invaded Kalinga, dealing a significant blow to the Gajapati Empire’s forces.

- Govinda Vidyadhara’s Rebellion (1541): The Gajapati Empire’s decline reached its pinnacle when Govinda Vidyadhara, a minister under Gajapati king Prataparudra Deva, rebelled and, in 1541, ascended the throne by murdering Prataparudra Deva’s two sons.

The Rise and Fall of the Bhoi Dynasty: A Tale of Conflict and Rebellion

The Bhoi dynasty, a short-lived reign in the annals of history, was established by Govinda Vidyadhara through a tumultuous coup in the year 1541. This dynasty’s reign was marked by internal strife, external conflicts with neighboring kingdoms, and a series of rebellions. In this article, we delve into the turbulent period of the Bhoi dynasty, exploring the key players, their actions, and the ultimate demise of this once-promising rule.

- The Ascension of Govinda Vidyadhara: Govinda Vidyadhara’s ascent to the throne was far from conventional. He seized power in a bloody coup, setting the stage for a dynasty that would face constant challenges and unrest throughout its existence. In 1541, he took the reins of the kingdom, heralding a new era marked by political instability.

- Raghubhanja Chhotray: The Nephew Turned Rebel: Among the earliest challenges faced by the Bhoi dynasty was the rebellion of Raghubhanja Chhotray, the nephew of Govinda Vidyadhara. Dissatisfied with the new regime, Chhotray took up arms against his uncle’s rule, adding to the dynasty’s woes. This rebellion was a precursor to a period of continuous conflict and division within the kingdom.

- The Unpopular Rule of Chakrapratap: Following Govinda Vidyadhara’s reign, his son, Chakrapratap, ascended to power. However, his rule was plagued by unpopularity and discontent among the subjects. Chakrapratap’s inability to garner support and maintain stability further weakened the Bhoi dynasty.

- The Rise of Mukunda Deva: In 1557, after Chakrapratap’s demise, a minister named Mukunda Deva seized the opportunity to rebel against the faltering dynasty. His actions culminated in the downfall of the last two Bhoi kings. Mukunda Deva emerged as a formidable force during this turbulent period, setting the stage for a major shift in power dynamics.

- The End of the Bhoi Dynasty: With the demise of the last Bhoi kings and the successful suppression of Raghubhanja Chhotray’s rebellion, Mukunda Deva declared himself the Gajapati of Odisha, effectively bringing an end to the Bhoi dynasty’s rule. This marked the conclusion of a short-lived and tumultuous chapter in the history of the region.

Mukunda Deva: The Last Independent Ruler of Odisha’s Turbulent History

In 1559, Mukunda Deva, also known as Mukunda Harichandana, ascended to the throne of Odisha in a tumultuous coup. Hailing from the Chalukya dynasty, he assumed leadership during a period marked by intense internal conflicts within the region. Mukunda Deva’s reign was defined by strategic alliances and unfortunate clashes.

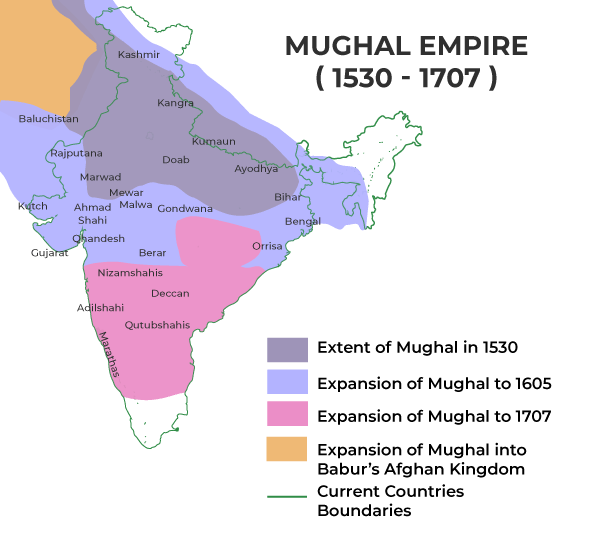

Recognizing the need for stability, Mukunda Deva forged an alliance with the formidable Akbar, positioning himself in opposition to Sulaiman Khan Karrani, the ruler of Bengal. In response to this alignment, Sulaiman Khan dispatched his son, Bayazid Khan Karrani, alongside his infamous general, Kalapahad, to conquer Odisha in 1567.

Mukunda Deva initially confronted these forces in the northern region but was compelled to withdraw when faced with a rebellion, which erupted shortly after he signed a treaty with the Sultan’s son. Tragically, Mukunda Deva met his end in a battle against the rebel forces led by Ramachandra Bhanja, a feudal lord who had revolted against his rule. In the midst of the turmoil, Ramachandra Bhanja himself fell victim to the conflict, succumbing to Bayazid’s treacherous actions.

Akbar, engaged in preparations for the invasion of Chittor, was unable to intervene in Odisha at the time. Consequently, Kalapahad embarked on a destructive rampage throughout the kingdom, devastating numerous temples and sacred sites. By the close of 1568, Odisha had fallen under the control of Sulaiman Khan Karrani, marking the end of an era of independence for the region.

During this tumultuous period, Ramachandra Deva I, the son of a general who had been imprisoned by Mukunda Deva, managed to escape from captivity and sought refuge in Vizagapatam. This escape in 1568 holds significant historical importance, as it symbolizes the conclusion of Mukunda Deva’s rule and the beginning of Odisha’s decline as an independent kingdom.

Odisha’s Historical Transformation under Sultan Sulaiman Khan Karrani

In the year 1568, Odisha underwent a significant shift in its governance when it fell under the rule of Sultan Sulaiman Khan Karrani, a prominent figure from the Karrani dynasty who ruled over the Sultanate of Bengal. Sultan Sulaiman Khan Karrani appointed Ismail Khan Lodhi of Prithimpassa as the governor of Orissa, entrusting him with the region’s administration.

This period saw a pivotal moment in Odisha’s history during the Battle of Tukaroi, situated in present-day Balasore. During this battle, Daud Khan Karrani suffered defeat and was forced to withdraw deeper into the territory of Odisha. The aftermath of this battle resulted in the Treaty of Katak, where Daud Khan Karrani conceded control of Bengal and Bihar, retaining only Odisha.

However, the stability of the treaty was short-lived, as it unraveled following the passing of Munim Khan, who had served as the governor of Bengal and Bihar until the age of 80. Seizing the opportunity, Daud Khan Karrani launched an invasion into Bengal, setting the stage for the consequential Battle of Rajmahal in 1576. In this battle, Daud Khan Karrani suffered defeat and met his demise through execution.

Transformation of Odisha under Mughal rule

In the year 1590, a significant historical event unfolded as Qutlu Khan Lohani, an officer serving under Daud, the Sultan of Bengal, made a bold move by declaring his independence and adopting the title of “Qutlu Shah.” This declaration did not go unnoticed, and it drew the attention of Raja Man Singh, the Mughal governor of Bihar. Recognizing the potential threat posed by Qutlu Khan, Raja Man Singh initiated an expedition to bring him under Mughal control.

However, fate had other plans, as Qutlu Shah’s reign was short-lived, cut short by his untimely demise before he could face the formidable Raja Man Singh. Following Qutlu Shah’s passing, his son Nasir Khan assumed leadership and, with limited resistance, acknowledged the sovereignty of the Mughal Empire. On the auspicious date of 15 August 1590, Nasir Khan paid homage to Raja Man Singh, cementing his allegiance to the Mughal rule.

In recognition of his loyalty, Nasir Khan was appointed as the Governor of Odisha, marking an important turning point in the region’s history. Under Nasir Khan’s leadership, a treaty was established, resulting in the cession of the territory in and around the revered city of Puri to the Mughal Empire. For a period of two years, Nasir Khan remained a faithful vassal to the Mughal Empire, upholding the terms of the treaty.

However, the course of history took a different trajectory as Nasir Khan’s actions began to deviate from the agreed-upon conditions of the treaty. In a troubling turn of events, he laid siege to the sacred Jagannath Temple of Puri, a move that provoked a swift response from Raja Man Singh. The conflict escalated, culminating in a decisive battle that took place on 18 April 1592, near what is now the town of Midnapore.

In this pivotal battle, Raja Man Singh emerged victorious, effectively quashing Nasir Khan’s insurrection and reaffirming Mughal authority in the region. By the year 1593, Odisha had fully come under the dominion of the Mughal Empire, becoming an integral part of the Bengal , a testament to the empire’s expansion and consolidation of power in this significant historical period

Transformation of Odisha under Akbar’s rule

In the historical annals of India, the reign of Raja Ramachandra Deva, the king of Khurda, marks a pivotal moment when he willingly accepted the suzerainty of Emperor Akbar. During Akbar’s rule, a policy of minimal interference in the affairs of local chieftains like Raja Ramachandra Deva prevailed. However, a significant shift in this policy occurred with the ascension of Jahangir to the Mughal throne.

Jahangir’s tenure as Emperor ushered in a new era for Odisha. Under his leadership, Odisha was designated as a separate Subah, or province, within the vast Mughal Empire. To administer this province, Jahangir appointed a governor bearing the prestigious title of Subahdar. This governor ruled in the name of the Mughal emperor, overseeing the governance and affairs of Odisha with a sense of central authority.

This transformation under Jahangir’s rule signified a departure from Akbar’s non-interference policy and marked the integration of Odisha into the broader administrative structure of the Mughal Empire. The appointment of a Subahdar was emblematic of the Mughal Empire’s growing influence in the region, laying the foundation for a new chapter in Odisha’s history within the grand tapestry of the Indian subcontinent.

Odisha under Jahangir’s rule

Quasim Khan’s governorship in 1606 marked a pivotal era in Odisha’s history. During this period, the region witnessed significant conflicts, with the Mughal armies, under the leadership of Kesho Das, launching an assault on Purusottam Deva, the King of Khurda. This confrontation resulted in a defeat for Purusottam Deva, who had to resort to offering his sister and daughter as dowries to secure peace.

In 1611, Kalyan Mal, the son of Todar Mal, assumed the role of governor in Odisha. Kalyan Mal, much like his predecessor, initiated an attack against Purusottam Deva, emerging victorious. Consequently, Purusottam Deva had to send his daughter into the Mughal harem as part of the terms.

The year 1617 witnessed a change in leadership, as Kalyan Mal was recalled to the court, and Mukarram Khan took over as the governor of Odisha. Mukarram Khan also aimed to confront Purusottam Deva, but the latter fled from Khurda to avoid further confrontation.

In 1621, Ahmad Beg assumed the role of governor in Odisha, taking the reins from his predecessors. It was during this period that Purusottam Deva passed away in exile in 1622, and his son, Narasimha Deva, succeeded him as the ruler of Khurda.

The historical records, as chronicled in the Madala Panji (temple chronicles), reveal that Prince Shah Jahan visited Odisha in 1623, shortly after his rebellion.

Ahmad Beg continued to serve as the governor of Odisha until 1628, marking the culmination of this intriguing chapter in the region’s history.

Odisha under Shah Jahan’s rule

In 1628, Shah Jahan ascended to the throne as the Mughal emperor, and he appointed Muhammad Baqar Khan as the governor of Odisha. During his tenure, Khan expanded his influence into the Golconda kingdom. However, in 1632, Khan was called back to the Mughal court.

Shah Shuja then took on the role of Subahdar of Bengal, a position he held from 1639 to 1660. From 1645 onwards, a deputy named Zaman Teharani served as the governor of Odisha. This marked a significant development as Orissa became the first top-level imperial province, or “subah,” added to Akbar’s original fifteen by Shah Jahan. Cuttack served as its administrative center, and it shared borders with Bihar, Bengal, and Golconda subahs, as well as various independent and tributary chiefs.

In 1647, a tragic event occurred when a Mughal general named Fateh Khan executed Narasimha Deva, a prominent figure in the region. This event left a lasting impact on the history of Odisha under Mughal rule.

Aurangzeb rule

In 1658, as Shah Jahan’s health declined, Dara Shikoh assumed the role of royal regent, setting the stage for a turbulent succession war that ultimately led to Aurangzeb’s victory in 1659. Aurangzeb proceeded to imprison his own father, who passed away in 1666. Amidst this period of uncertainty within the Mughal empire, various chieftains in Odisha seized the opportunity to declare their independence.

During Aurangzeb’s reign from 1660 to 1667, he appointed Khan-i-Duran as the governor. Khan-i-Duran’s rule was characterized by the suppression of numerous rebel chieftains and the subjugation of Mukunda Deva I, the reigning monarch of Khurda at that time.

Murshid Quli Khan rule

In 1707, with the passing of Aurangzeb, the Mughal Empire’s influence over Odisha began to wane. Taking the reins in 1714, Murshid Quli Khan assumed the role of governor in Odisha, and later in 1717, he ascended to become the Nawab of Bengal. While pledging loyalty to the Mughal emperor, Khan effectively ruled as an autonomous leader. He implemented various strategies to boost revenue, including the creation of numerous new Jagirs. Following his demise in 1727, his son-in-law, Shuja-ud-Din, assumed the mantle of Nawab in Bengal, having previously served as Murshid’s deputy in Odisha. During Shuja-ud-Din’s tenure, several territories were lost to neighboring kingdoms

Shuja-ud-Din’s rule

In the annals of Odisha’s rich history, the year 1727 marked a significant turning point. Taqi Khan, the son of Shuja-ud-Din, assumed the role of governor, setting the stage for a series of dramatic events. His leadership would ultimately shape the destiny of this region.

Taqi Khan’s tenure was marked by a confrontation with Ramachandra Deva II, a pivotal figure in this historical narrative. A war erupted between them, resulting in the imprisonment and conversion of Ramachandra Deva II to Islam. This event left an indelible mark on the history of Odisha.

During one notable incident, Ramachandra Deva II ventured to Puri to witness the grand car festival. However, Taqi Khan viewed this move as an encroachment on Khurda, leading to Ramachandra Deva II’s hasty departure. In the wake of this, Bhagirathi Kumar, the son of Ramachandra Deva II, was declared as the new king by Taqi Khan, further reshaping the region’s political landscape. Tragically, Taqi Khan’s life was cut short in 1734, but his reign left a lasting legacy in the form of several Islamic monuments that were constructed in Odisha during his rule.

Following Taqi Khan’s demise, the mantle of leadership passed to Murshid Quli Khan II, also known as Rustam Jung. He served as the deputy governor under Shuja-ud-Din and was his son-in-law. Rustam Jung ushered in a period of relative tolerance, allowing worship in Puri. He even cemented ties by marrying his daughter to Ramachandra Deva II. In 1736, Padmanava Deva was installed as the king of Khurda, but the dynamics shifted in 1739 when Birakesari Deva, Ramachandra Deva II’s son, assumed the throne. This change in leadership reflected the intricate political intrigues of the time.

In 1739, Shuja-ud-Din passed away, making way for his son, Sarfaraz Khan, to assume power. However, Sarfaraz Khan’s rule was short-lived, as he met his demise in the Battle of Giria at the hands of Alivardi Khan. Rustam Jung attempted to avenge this defeat but found himself on the losing side when confronted by Alivardi Khan. The latter, despite his victory, did not enjoy widespread popularity among his subjects.

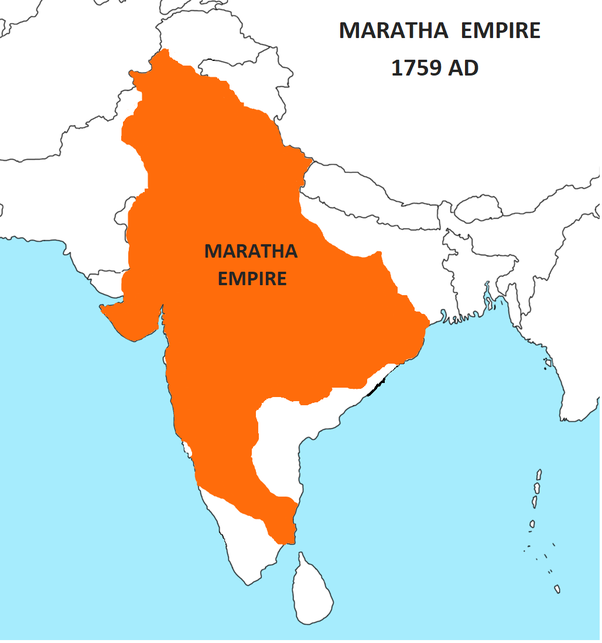

The Marathas entered the scene in 1742, launching a series of raids on Alivardi Khan’s territory. Rustam Jung and his allies supported these raids, employing swift hit-and-run tactics that came to be known as “bargis.” Alivardi Khan, unable to thwart these relentless assaults, eventually ceded Odisha to Raghoji I Bhonsle in 1751.

During this tumultuous period, the idols of Jagannath and other revered deities from the temple were repeatedly removed and hidden to protect them from iconoclasm.

The history of Odisha during this era is a compelling tale of shifting alliances, religious conversions, and the impact of external forces. It is a testament to the region’s resilience and its enduring cultural heritage.

Historical Significance of Maratha Rule in Orissa and Its Impact on Trade and Culture

In 1751, the Marathas gained control over Orissa’s administration, with the river Subarnarekha marking the boundary between Bengal and Maratha-ruled Odisha.

Under Maratha’s rule, Orissa’s status as a pilgrimage destination, particularly the Jagannath Temple, was elevated. They prioritized the upkeep and restoration of religious sites, introducing a pilgrim tax in Puri for revenue, which was exempted for the destitute. The Marathas also invested in road construction, and housing development, and even ventured into postal services. Nevertheless, external trade dwindled in Maratha-held Orissa, as British dominance in the Bengal region and their control over maritime trade in the Bay of Bengal caused a significant decline in local grain and commodity exports.

Orissa experienced a flourishing of literature and poetry during the Maratha rule, thanks to the support of local chiefs and Maratha rulers. The period witnessed significant advancements in Kavya and Padya literature, encompassing both prose and poetry.

Recognizing Orissa’s strategic trade position, Britain seized the region in 1803 during the Second Anglo-Maratha War, as it lay strategically between British-held Bengal and Madras.”

Evolution of European Settlements in Odisha: From Portuguese Factories to British Endeavors

The Portuguese, in a significant historical milestone, became the first Europeans to construct factories in Odisha. Their settlement found its home in Pipili, situated within the Puri district. This initiative marked the initiation of European presence in the region, laying the foundation for future developments.

Subsequently, the British entered the scene, commencing their own settlement in Hariharpur as early as 1633. Their presence was made possible with the permission of the Mughal administrator of the time. This settlement was primarily established for the purpose of trading cotton goods. However, the endeavor faced significant challenges that led to its eventual decline. The harsh climate and the constant threat of Portuguese and Aracanese pirates took a toll on its sustainability.

A pivotal turning point in Odisha’s history occurred in 1765 when Lord Clive, a key figure in the British East India Company, acquired the Diwani rights of Bengal, Bihar, and Odisha from the titular Mughal emperor, Shah Alam II. However, it’s crucial to note that this acquisition only encompassed the Midnapore district of Odisha. The remainder of the region had already fallen under the domain of the Marathas.

Lord Clive made earnest attempts to negotiate the acquisition of Odisha from the Marathas, but these efforts did not bear fruit during his tenure. Following his leadership, Warren Hastings, his successor, continued the negotiations with the Marathas, endeavoring to extend British influence over this strategically vital territory.

Historical Milestones in Odisha: From British Era to Independence

In 1803, Colonel Harcourt, leading the Presidency armies, embarked on a journey from Northern Circars, arriving on August 25th. His mission was to liberate the region from Maratha influence, and on September 8th, he commenced his march with 5000 soldiers from Ganjam. By September 18th, Harcourt had taken control of Puri, while on September 21st, a second force landed at Balasore and sent reinforcements to aid in the siege of the fort at Cuttack. The fort of Barbati fell on October 14th.

On December 17, 1803, after the Battle of Laswari, Raghoji II Bhonsle of Nagpur signed the Treaty of Deogaon (also known as Deogarh) with the British East India Company. He relinquished control of Cuttack province, which included the coastal Mughalbandi plain, Garhjat, princely states of Western Odisha, Balasore port, and parts of Midnapore district in West Bengal. This region was governed by the British as a division of the Bengal Presidency until 1912, with Cuttack as its administrative center, while the princely states remained under indirect rule.

In 1804, Jayakrushna Rajaguru Mohapatra, known as Jayi Rajaguru, the royal preceptor to Mukunda Dev II, led a rebellion against British rule, marking the first uprising against British authority in Orissa. Although the Presidency armies, aided by local chiefs, ultimately suppressed the rebellion, both Jayi Rajaguru and the Raja were captured. On December 6, 1806, Jayi Rajaguru was executed in Midnapore.

In 1817, the British had to quell the Paika rebellion. The Paika were a land militia exempt from taxes in exchange for their services but were discontented with the new British land laws. They were led by Bakshi Jagabandhu, a commander of the king of Khurda.

Surendra Sai from the Sambalpur region initiated a rebellion against the British in 1827, and during the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the princes of Odisha did not participate in the conflicts.

In 1866, Odisha suffered a devastating famine called “Na Anka Durvikhya,” resulting in an estimated death toll of around one million across various regions. During the famine, Babu Bichitrananda Das and Gouri Shankar Roy decided to publish a magazine in Odia. The first issue of “Utakala Deepika” was released on August 4, 1866, addressing the famine issue. This marked the first independent publication in Odia, despite Christian missionaries having established a printing press in Cuttack in 1838.

In 1870, Madhusudan Das became the first person from Odisha to attain a graduate degree, eventually acquiring a law degree in 1878. He emerged as a prominent leader of the state.

After Madhusudan Das returned to Cuttack in 1881, the Utkal Sabha was established in 1882, signaling the commencement of political activities in Odisha. In 1888, during the visit of the Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal, a durbar was held in Cuttack where the Utkal Sabha, led by Gouri Shankar Roy, advocated for bringing Odia-speaking territories under one administration.

In 1903, the Utkal Union Conference was founded, and in 1912, Odisha and Bihar were separated from the Bengal province to form a new single province. The Orissa Tenancy Act was introduced in 1912, securing better rights and treatment for ryots in the region. In 1913, Sashi Bhusan Rath started publishing the first Odia daily newspaper, “Asha,” from Berhampur. Gopabandhu Das was the editor and wrote its editorials until 1919. In 1915, Gopabandhu Das began publishing a magazine called “Satyabadi” to promote Odia literature and culture, and on October 4, 1919, he initiated his own weekly newspaper, “Samaja.” In 1914, the revolutionary Bagha Jatin moved to a hideout in Kaptipada village in Mayurbhanj. On September 9, 1915, Bagha Jatin and his companions engaged in a 75-minute gunfight with colonial authorities, leading to Bagha Jatin’s demise on September 10, 1915.

In 1885, the Indian National Congress was established, and in 1920, it adopted the reorganization of provinces based on linguistic basis as one of its agendas. This inspired leaders in Odisha to form an Odisha Congress Committee and demand a separate province for the Odia-speaking population. In 1923, the Bhubanananda Odisha School of Engineering was founded in Cuttack, becoming the first technical diploma institution in the region. In 1927, Cuttack and Balasore districts experienced abnormal floods for the third consecutive year, affecting around 28,756 families.

On April 6, 1930, a group of volunteers marched from Cuttack to Inchudi in Balasore, where on April 12, they defied the British salt tax law by producing salt. On April 1, 1936, Odisha was granted the status of a separate province, celebrated annually as Odisha Day (Utkala Dibasa) on April 1st. In 1936, Odisha comprised six districts: Cuttack, Puri, Balasore, Ganjam, Koraput, and Sambalpur. On October 11, 1938, a 12-year-old ferry boy named Baji Rout was shot dead by policemen in Dhenkanal district when he refused to ferry them across the river. In 1943, Utkal University was founded.

In March 1946, the foundation stone for the Hirakud Dam was laid by the Governor of Odisha, Sir Hawthorne Lewis. The same year, the Central Rice Research Institute (CRRI) was established in Cuttack to prevent famine situations like the Bengal famine of 1943. On July 22, 1947, Biju Patnaik was rescued. Indonesian Prime Minister Sutan Sjahrir and Vice President Mohammad Hatta were flown to Singapore from behind Dutch lines in a Douglas C-47 Skytrain, disguised as crew members, ultimately reaching India on July 24th.

History of Odisha after Republic India

Odisha, a land steeped in history, witnessed a series of remarkable events that shaped its destiny from 1947 to now. Let’s take a journey through time to understand the key turning points in the state’s history.

1947-1950: A New Beginning

- In May 1947, Harekrushna Mahatab assumed office as part of the Congress ministry.

- The decision to make Bhubaneswar the new political capital of Odisha was taken in 1946.

- German architect Otto Königsberger was entrusted with designing Bhubaneswar after India gained independence.

- Construction of the Hirakud Dam commenced in 1948.

- Odisha integrated 24 princely states and was divided into 13 districts in 1949.

- Mahatab resigned in May 1950 to join the Indian Cabinet, and Nabakrushna Choudhuri took over as Chief Minister.

1951-1961: Development and Progress

- Biju Pattnaik‘s donation to UNESCO led to the establishment of the Kalinga Prize in 1951.

- In 1952, Nabakrushna Choudhuri became Chief Minister again.

- The Hirakud Dam was completed in 1953, marking a significant milestone.

- Plans for the Rourkela Steel Plant were made in collaboration with West Germany in 1953.

- Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru inaugurated the Hirakud Dam in 1957.

- Harekrushna Mahatab returned as Chief Minister in 1957, and a coalition government took charge in 1959.

- President’s rule was imposed in 1961 after the coalition collapsed.

1961-1977: Political Shifts and Key Events

- The Legislative Assembly’s new building was inaugurated in February 1961.

- The Regional Engineering College, Rourkela, was founded on India’s Independence Day in 1961.

- The foundation stone for the Paradip Port was laid in January 1962.

- In 1966, the Balimela Reservoir project began.

- Biju Patnaik’s resignation was part of the Kamaraj Plan in August 1963.

- Mahatab formed the Jana Congress in 1966.

- The Swatantra Party and Orissa Jana Congress formed a coalition government after the 1967 Assembly polls.

- In 1971, a coalition government led by Bishwanath Das was formed.

1972-1980: Changing Leadership

- Nandini Satpathy assumed the role of Chief Minister in June 1972.

- She resigned in 1973 and formed her second ministry in 1974.

- Binayak Acharya briefly held office in 1976.

- The Janata Party remained in power from 1977 to 1980.

1980-1994: New Horizons

- Janaki Ballabh Patnaik became Chief Minister in 1980.

- NALCO, Angul, was founded in collaboration with Pechiney in 1981.

- In 1984, Indira Gandhi’s visit to Bhubaneswar was tragically followed by her assassination.

- Patnaik was re-elected as Chief Minister in 1985.

- The Agni-I missile was tested in 1989.

- Hemananda Biswal took office in December 1989.

- Rabi Ray served as the Speaker of Lok Sabha from December 1989 to July 1991.

1990-2023: Transformative Changes

- Ranganath Misra became the 21st Chief Justice of India in 1990.

- The Janata Dal government, led by Biju Patnaik, took power in 1990.

- Odisha witnessed significant district expansions in the early 1990s.

- Ranganath Misra became the first chairman of the National Human Rights Commission of India in 1993.

- Janaki Ballabh Patnaik returned as Chief Minister after the 1995 Assembly polls.

- In 1999, Australian missionary Graham Staines and his sons were tragically murdered.

- A devastating cyclone struck Odisha in 1999, causing immense damage.

- Naveen Patnaik assumed the Chief Minister’s office in March 2000.

- In 2014, Odia language was granted classical language status, a significant cultural recognition.

These historical milestones demonstrate the resilience and progress of Odisha, highlighting its transformation over the decades. Each era brought new challenges and opportunities, shaping the state into what it is today.